Defy Ventures brings the gospel of entrepreneurship to an unlikely place: prisons.

The nonprofit company founded by Catherine Hoke says it is dedicated to helping formerly incarcerated people start their own businesses and stay out of prison. “Transform the hustle,” the company’s tagline encourages.

Defy has received grants from Google and the conservative Koch brothers. Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg wrote a foreword to Hoke’s new memoir. Former U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara called Hoke’s work “incredibly inspiring” on his podcast. Hoke’s project even has White House interest: She had a call with Jared Kushner’s office in January to discuss a visit about prison reform.

But while Defy woos Silicon Valley and Washington, D.C., scandal has rocked the company’s leadership. Last month, Defy fired its president after he blew the whistle on allegations of sexual harassment by Hoke and fraudulent statistics exaggerating the program’s successes.

Hoke describes Defy as a second chance—not just for people with criminal histories, but for herself. A former employee at a private equity firm, Hoke left Wall Street to launch a business skills-training program for Texas prisoners in 2004. In 2009, she was banned from Texas prisons after she was discovered to have had sexual relations with four program graduates.

She founded Defy the following year, making a fresh start in New York. Since then, Defy has expanded its work to include classes for current and formerly incarcerated people. The program has operated from 15 prisons, and teaches post-release classes online, as well as in person in New York, California, Colorado, and Nebraska. Less than 5 percent of Defy students return to prison, the company claims as part of its pitch to donors.

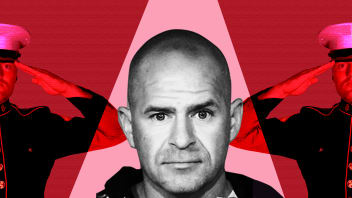

In December 2017, the company brought on Roger Gordon as its new president. Gordon is a lawyer who previously founded a food bank assistance company and chaired a nonprofit that employed more than 100 formerly incarcerated people. But by mid-January, Gordon said he had serious concerns about Hoke’s conduct and the success rates Defy claimed in presentations to donors.

On Jan. 16, Gordon took his concerns to the chair of Defy’s board. Three days later, he says, he was suspended, ordered to turn over all notes he’d taken on his first days of the job, and ordered not to talk to employees. While suspended, he took his concerns to officials at New York’s Walkill Correctional Facility where Defy has taught classes. Those concerns were documented in a letter reviewed by The Daily Beast. On Feb. 26, Defy fired Gordon citing his outreach to donors and employees.

Contacted by email earlier this month, Defy did not answer The Daily Beast’s questions on Gordon’s specific allegations, but instead issued a statement on Gordon’s firing, saying the company had hired a law firm to investigate his claims.

Gordon was terminated for “communicating with donors and supporters of the organization in a manner that the Board believed was damaging to Defy and inconsistent with Mr. Gordon’s fiduciary obligations” against the board’s orders, it said in a statement.

Regarding Gordon’s allegations, “our investigation is ongoing,” the board said in its statement. “But we now feel compelled to say, based on our preliminary assessment, that Mr. Gordon’s allegations do not appear to be supported by other members of the organization or by other evidence available to the investigators.”

But in interviews with The Daily Beast, other former employees supported some of Gordon’s allegations.

Defy settled a complaint brought by a female former employee who said Hoke “reached her hand up the employee’s skirt twice at a company party,” according to Gordon’s letter to prison officials.

“The employee signed an NDA [nondisclosure agreement] prohibiting her from disclosing the incident or the existence of the NDA to anyone except the CEO, her husband or the COO,” Gordon’s letter continued. “Two employees who witnessed the assault were forced to relinquish their personal mobile phones and passwords” and were questioned by an attorney from Gordon & Rees.

The lawyer involved did not comment on the allegations. A former employee who spoke with The Daily Beast supported Gordon’s claims that two witnesses had been made to surrender their phones.

It wasn’t the only time Hoke was accused of sexual harassment at Defy.

A former Defy client, Kenneth Maxwell, sued Hoke in 2015 alleging he was forced out of the program over his “refusal to consummate a personal and sexual relationship” with Hoke, according to his complaint. The lawsuit was dismissed after Maxwell failed to serve defendants with a summons and complaint.

Another female employee told The Daily Beast Hoke sexually harassed her during a business trip in 2014, insisting the woman share a bed with her.

“When we checked in to the Vertigo Hotel, the reserved room only had one king-size bed, which Catherine and I both occupied despite my repeated suggestions that I sleep on a cot,” the female former employee wrote in notes she shared with The Daily Beast.

Yet the woman wrote that Hoke warned about cohabitating with male coworkers.

“Catherine was clear about expectations when traveling with male Defy staff members, specifically that we were not to be in the same room with the door closed, and that ‘corporate fucking’ was not permitted,” the woman wrote.

Hoke repeatedly warned “no corporate fucking,” two other former employees told The Daily Beast.

The former Defy staffer who accompanied Hoke on the trip also quoted Hoke telling her “she ‘doesn’t usually like blondes, but that I am really hot.’” She also wrote that Hoke said she and her husband “would try to ‘gross each other out’” by imagining a former employee masturbating, and that Hoke was sad she had to share a room on the trip “because she wasn’t able to bring her toys along.” On another occasion, the former employee wrote, Hoke told her “she was '‘totally checking [me] out’ and that I have a ‘nice little ass.’”

On another occasion, Hoke allegedly asked a Defy volunteer about his relationship status. “After he disclosed to her that he was single, Catherine motioned to me and asked him ‘What about her?’” the former employee wrote.

Contacted last month, a source close to Sandberg told The Daily Beast that Sandberg was unaware of the allegations against Hoke. The person pointed to Sandberg’s previous calls to investigate any accusations of sexual harassment.

In his letter, Gordon also said the company had been accused of pocketing money from prospective students who never made it into the program.

“There have been allegations that Defy has collected application fees from students without intending to admit them and that winners of in-prison business plan competitions do not receive the cash prizes they are promised,” he wrote in his letter. “Instead, they have been asked to reimburse Defy for program costs and to sign over the money.”

Defy does not appear to advertise its prices on its website. Asked for the company’s tuition rate, a Defy representative told The Daily Beast “we do not charge tuition.”

But when The Daily Beast pointed to former clients who claimed to have paid for hundreds for classes, and to a Defy fundraising campaign to raise “scholarships” for clients, Defy did not answer further questions.

In his lawsuit, Maxwell claimed to have been “required to pay a monthly tuition in the amount of $200” beginning around June 2014. Another former client, who used Defy’s program around the same time as Maxwell, told The Daily Beast the program cost “$700 for the course which was online.” Defy’s online courses were largely taught from pre-recorded videos, multiple former employees said. Costs piled up, the former client alleged. In the end, “it was actually more like $1,200. I believe $100 month to month… But I chose to pay upfront for $700.”

Those figures align with a fundraising campaign on Defy’s website, which encourages monthly donations. The second-lowest tier of recommended donations is “$1,200 (or $100/month): Provide one scholarship to a post-release [student] enrolled in our Academy training program.”

Another former Defy client told The Daily Beast she received some form of scholarship, although the exact value was never clear to her.

“I was given a scholarship but I was never told how much it was. I was the first person the receive this in the class,” the client, who attended Defy in 2014, said.

Defy courts donors with prison visits, where the company brings supporters to meet incarcerated students. During these visits, Defy conducts one of its hallmark exercises: a drill called “Step to the Line” in which potential investors (“who are almost all white, college educated and well off,” Gordon wrote) face off against students, across a long line of tape on the floor. Hoke calls out increasingly personal prompts, like “step to the line if your first arrest was before the age of 10,” she recounts in her memoirs.

The ice-breaker is meant to illustrate privilege, revealing how the incarcerated faced greater childhood adversity than the visitors. It’s also an effective fundraising tool, Gordon claimed. “Defy will take the same group of inmates through the exercise three different times for three different groups of donors,” he wrote.

Every year since at least 2012, Defy has made more money than the previous year, tax records show. But 2016 was a banner year, even by those standards. The company took in more than $5 million, more than twice its previous record from 2015.

Hoke’s salary has increased, too. Defy’s nonprofit tax returns show Hoke’s 2016 salary as $150,000, plus more than $20,000 in other compensation from Defy or related ventures. In 2015, her salary had been $139,137. In 2015, her husband Charles’ income also started appearing on the company’s tax return, listed as $118,750. In 2016, it jumped to $135,857, plus more than $11,000 in other compensation.

Defy fundraises on its successes, including its stated prison recidivism rate of less than 5 percent for the more than 5,500 students it claims to have served. But some former employees expressed doubts about the figure.

“There is no way to arrive at this figure through any consistent and doctrinally sound methodology,” Gordon alleged in his letter to the board. “Rather, it appears to be arrived at by selectively including program participants and by broadly defining success. More specifically, only the relatively few participants who complete the entire program are checked for recidivism and even then data is selectively omitted.”

Another former employee accused Defy of using misleading numbers. The “students served” metric also included people who had started the enrollment process, but did not attend classes, they told The Daily Beast.

“If they signed up for the program, literally went on and created username and a password, it counted as we served them,” the former employee said, likening the process to creating an email account.

And even clients who made it to the classroom had a high turnover rate. The former employee described observing a Defy class of approximately 100 people, from which he estimated 20 to 30 students graduated. Only those who graduated were factored into some of Defy’s statistics, the former employee claimed.

“When it came to job placement, recidivism, or any success metric they broadcast, they only used the percentage from graduates, not from everyone they said they served.”

Maxwell, the former client who sued Hoke, made similar allegations on a now-defunct website. (He did not respond to requests for comment.)

“Defy Graduated just 8 students into its Third and Final phase of its Entrepreneurial Program on March 26, 2015, in a class that began in October of 2014 with 55 participants,” Maxwell alleged.

Regarding Defy’s recidivism rate, “DEFY’s numbers only reflect current participants in its program, and not those that the organization has either expelled, or participants who have otherwise separated from DEFY,” Maxwell wrote. “The organization simply does not track former incarcerated individuals who are no longer on DEFY’s active rosters and, thus, the statistics they they point to are simply misleading.”

Some Defy graduates boasted positive experiences with the company. Coss Marte, a Defy graduate who helps judge some of Defy’s business pitch competitions, said Defy helped him launch his highly successful fitness company ConBody, which he first envisioned while incarcerated.

“My experience with Defy was holistic, an incredible partnership and reentry program,” Marte told The Daily Beast. He praised the trainers in his class, whom he said helped him get his business online after he was disconnected from computers while incarcerated. “I’d contact a Defy staffer at 8 at night and they’d be on it. I never got pushed back. It was open hands. People really cared.”

Marte’s is a standout success story, featured on Defy’s website and in Hoke’s memoirs. But Gordon alleged that many of the endeavors Defy claims to have helped launch never went much further than a student registering a business name with the state.

“A job is said to have been created whenever a business is created regardless of whether it generates any revenue or pays any salaries,” he wrote in his letter. “In the time I was at Defy, no one could provide me with a list of businesses started by program participants. Instead, the same ‘stars’ are showcased over and over again.”

Gordon was fired Feb. 26, the day Hoke’s released her memoir, A Second Chance: For You, For Me, and For the Rest of Us.